Section 5: The 1800s

The 19th century largely focused on two themes: the growth of the nation’s size and the ability of Americans to participate in its freedom. The nation continued to expand westward, particularly due to territorial gains in the Louisiana Purchase and after the Mexican-American War.

Section 5: The 1800s

Study Guide

Section 5.1: Purchasing the Louisiana Territory

Section 5.2: Wars of the 19th Century

America engaged in a variety of wars in the 19th century. The most important of these were the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War. British efforts to effectively draft former British subjects, now American citizens, into serving in the British Navy against Napoleon eventually led to conflict with Britain in the War of 1812. Conflict-related to the acquisition of the former Mexican province of Texas led to the Mexican-American War in 1846. Perhaps most importantly, the United States of America engaged in a Civil War when southern states sought to secede to protect the institution of slavery. Finally, the brief Spanish American War in 1898 put an end to Spanish colonial presence in the Western Hemisphere.

Section 5.3: The Civil War and the End of Slavery

Over the course of the 19th century, slavery polarized American politics. Where once most political leaders from across the country had looked forward to the day slavery would die out, in the early 1800s Southerners such as John Calhoun began defending it not as a necessary evil but as a positive good, even for the slaves themselves. In the North, the abolitionist movement gained traction and grew increasingly intense in its rhetoric, as members of the movement argued for the immediate and complete elimination of slavery in the United States. Many other Americans, especially in the North, sought to arrest slavery’s growth in order to bring about its eventual collapse, and thus the newly formed Republican Party sought to end slavery in federal territory (that is, land that had not yet become a state).

Southerners, long used to using the power of the federal government to protect slavery over the protest of anti-slavery Northern states, feared the loss of this power. Thus, they responded to the victory of Abraham Lincoln and the anti-slavery Republican Party in 1860 by seceding from the Union. This triggered the Civil War.

The Civil War began when Confederate forces fired on the Union base at Fort Sumter in 1861. The war, which many expected to be over quickly, rapidly became a stalemate. Eventually, however, Union forces began amassing victories, such as the Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg, Maryland) in 1862, the Battle of Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) and Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi (both 1863). General William T. Sherman’s march through the South demoralized Confederates, while the military strategy of the Union’s overall commander, Ulysses Grant, to cut off the Confederacy by focusing on the western front proved successful. Eventually, the leading Confederate General, Robert E. Lee, surrendered his army to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse.

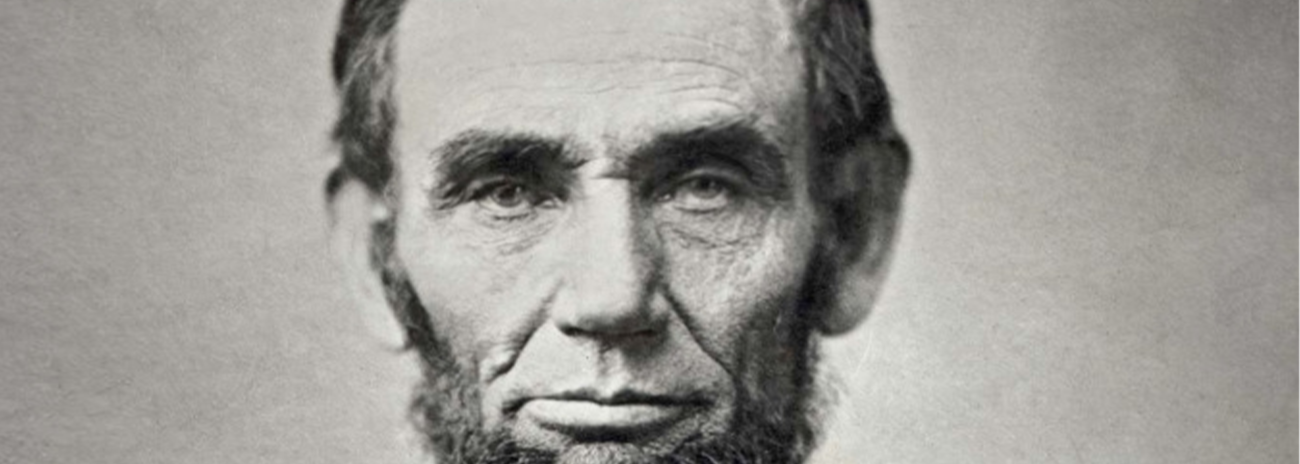

Abraham Lincoln led the United States during the Civil War and is credited with saving or preserving the Union. In addition, Lincoln freed the slaves in Confederate states with the Emancipation Proclamation while also helping convince Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, which decisively abolished slavery in the entire country. Lincoln did not see the results of these victories, however, as he was assassinated at war’s end by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer who raged at Lincoln’s support for black suffrage.

“…this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom -- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

- Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address, 1863

Soon after, Congress sought to deliver on that “new birth of freedom” through the Fourteenth Amendment, arguably the centerpiece of the post-war period known as Reconstruction. While the Bill of Rights initially only protected individuals from the federal government, the Fourteenth Amendment extended these protections to individuals against state governments as well. Ratified in 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment also required that states offer equal protection of the laws and “due process” to all within their boundaries, and guaranteed that, with very few exceptions, all who were born within the United States would be citizens, thus ensuring black Americans would-be participants in the American political society.

One more Reconstruction Amendment, the 15th Amendment ratified by the states in 1870, prohibited discrimination in voting on account of race; in other words, all male citizens could have the right to vote.

Section 5.4: Women’s Suffrage

Around the same time, the women’s rights movements sought to extend political and civil equality to women, in part by securing property rights and women’s suffrage (voting.)

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) is most famous for her efforts to secure women’s suffrage, but her fights for civil rights and women’s right to equality also included her efforts to secure racially integrated schools and women’s access to higher education, as well as abolitionism early in life. She was also a close ally of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had helped draft the Seneca Falls Declaration arguing for the extension of the promises of the Declaration of Independence to women. Other leaders in the women’s rights movement were Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Lucretia Mott, and Lucy Stone. Their dream of women’s suffrage throughout the United States was achieved with the 19th Amendment in 1920.